This text is chapter five of Relational Grace: The Reciprocal and Binding Covenant of Charis, by Brent J. Schmidt. The book is available free as a PDF, or for $21.95 as a print on demand book from BYU Studies.

About the book

In ancient Greece and Rome, charis was a system in which one person gave something of value to another, and the receiver gave service, thanks, and lesser value back to the giver. It was the word used to describe familial gifts, gifts between friends, gifts between kings and servants, and gifts to and from the gods. In Rome, these reciprocal transactions became the patron-client system.

Charis (grace) is the word New Testament authors, especially Paul, sometimes used to explain Christ’s gift to people. But what is the nature of the gift? Since the fifth century, a number of Christian scholars have taught that grace is something bestowed by God freely, with little or nothing required in return. This book sets out to show that “free grace” is not what Paul and others intended.

The practice in the ancient world of people granting and receiving favors and gifts came with clear obligations. Charis served New Testament authors as a model for God’s mercy through the Atonement of Jesus Christ, which also comes with covenantal obligations. Knowing what charis means helps us understand what God expects us to do once we have accepted his grace.

Chapter Five: Paul’s Use of Charis and the Concept of Reciprocity

As a Roman citizen and as a brilliant and learned Greek-speaking apostle, Paul must have intimately understood the Roman institutionalization of reciprocity in the patron-client system. His Roman gentile converts also intimately understood patronage. For this reason Paul places great emphasis on the fact that grace comes from Christ—and that Christ’s grace was not a corruptible monetary exchange like the increasingly unreliable Roman patron-client relationships of his time. God always reciprocates with his children. Paul stood in awe and often marveled that Christ and God offer humans grace at all (Eph. 1–3, for example). Their condescension from their lofty position makes their offer more asymmetrical than any earthly offer could ever be. The crucial point is that Paul did not teach that grace is a one-way, one-time, permanent gift from Christ to mankind. Paul did not reject the notion of reciprocal covenants. These covenants vertically bind man to God through obligations to keep his commandments.

Paul was also a devout Jew. As a Mediterranean society, the Jews were not immune to the influences of reciprocity and patronage. With a focus on worship of God, the Torah taught Jews to love and be loyal to one another as brothers, and the ways this ideology meshed with patronage were complex. For example, Jewish sage Ben Sira “assigns religious value to the presentation of benefits to friends . . . as a way of celebrating God-given bounty. Ben Sira strongly approved of the acquisition of social dominance, especially by sages or the righteous and wise.”[1] Paul drew on both his Jewish and Roman backgrounds to teach about grace.

This chapter analyzes many of Paul’s uses of grace in order to gain an understanding of what he meant in his first-century AD context. A detailed study of Paul’s relationship with groups and individuals mentioned in his epistles demonstrates that Paul innately understood the social conventions of benefaction, and this understanding must have informed how he used charis. Paul was the founder of communities and became the guide, legislator, educator, and benevolent defender of his communities: he became their patron and entered into charis relationships with them. I will argue in this chapter using dozens of examples from Paul’s many writings that he understood, respected, intended, and promulgated the social conventions of reciprocity to preach the gospel. As will be demonstrated below, Paul used the term charis according to its proper reciprocal Mediterranean social conventions.[2]

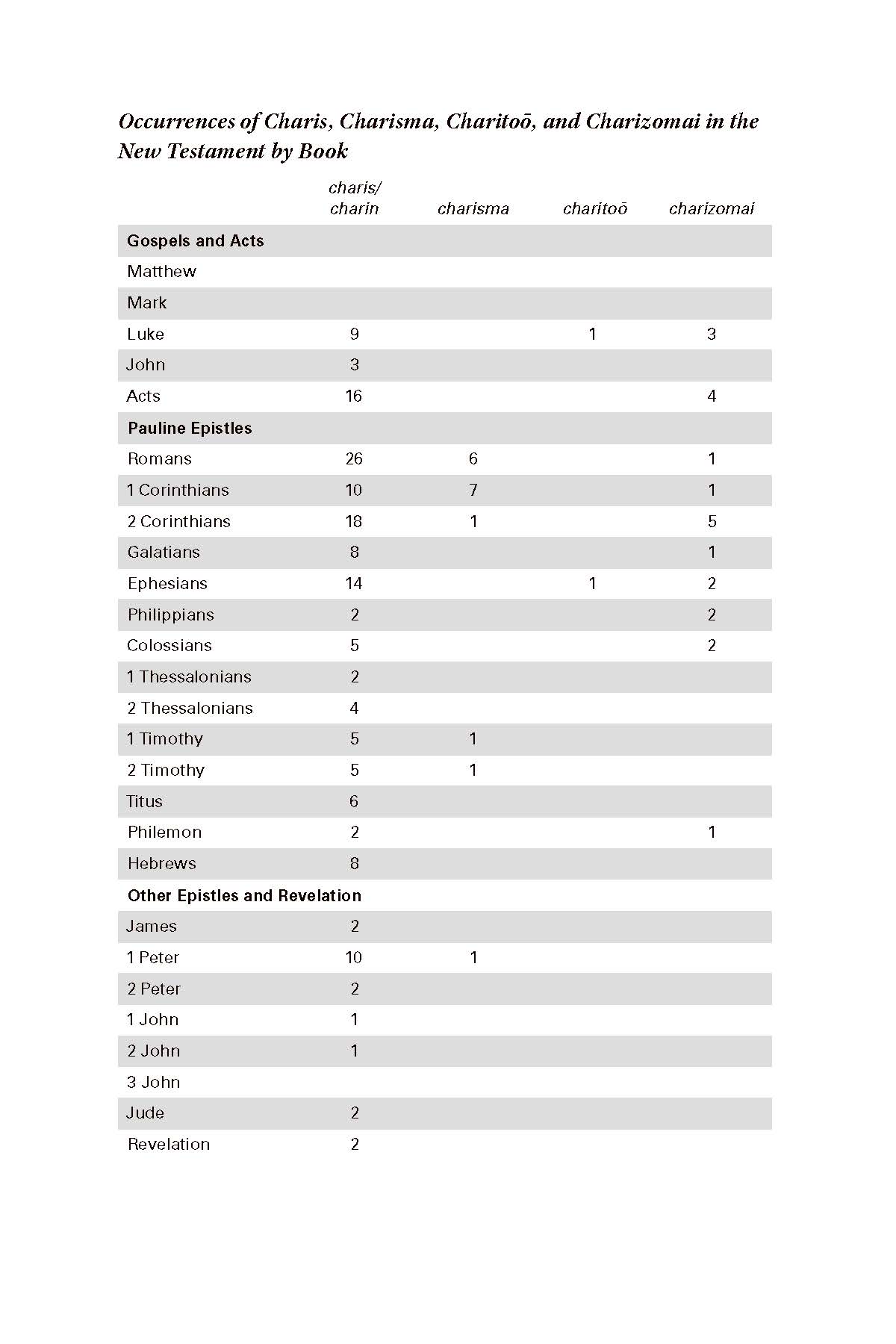

For the purposes of this study, I attribute all the writings associated with Paul as having been written by him.[3] At this point, it will be useful to have an overview of the use of the word charis and its related words in the whole New Testament. This chart shows the occurrences of charis, charin, charizomai, charisma, and charitoō as reported in “KJV New Testament Greek Lexicon.” There are 157 occurrences of charis in the New Testament,[4] translated in the King James Version as favor, grace, gracious, credit, thank, thankful, thankworthy, acceptable, gratitude, pleasure, liberality, and bounty. Where charis is being used as an adverb (charin) it is translated as because of, for this reason, for the sake of, on account of, and wherefore. The word charisma occurs 17 times and is translated as gift, free gift, and spiritual gift. Charitoó occurs twice and is translated as favored and accepted. Charizomai occurs 22 times and is translated as give, forgive, hand over, deliver, give up, grant, freely give, and bestow. The list of all verses using these words can be found online.[5]

This chart shows where these words are used in the New Testament. It is clear that Paul used charis and its related words more frequently than other New Testament authors, and for this reason we will study works attributed to him first.

This chapter will review charis by topics and show that Paul used the word charis to mean God’s gift, power from God, victory over physical and spiritual death, and, most frequently, as a greeting and expression of hope that Christians would accept God’s grace. As will be shown, this gift comes with expectations of performing service and acting righteously.

The Gift of Grace Invites Service

As did other ancient writers,[6] Paul utilized the word and the idea of grace as a vehicle to teach the importance of service. In Galatians 1:15–16, Paul teaches that he was invited by God’s grace to serve by preaching the gospel and he was set apart to do so: “God, who had set me apart before I was born and called [kalesas] me through his grace, was pleased to reveal his Son to me, so that I might proclaim him among the Gentiles” (NRSV).[7] Many translations such as the NIV translate the Greek word kaleō to mean “call” in this verse, but I believe kaleō is better translated into English as “invited” because charis gifts do not “call” individuals to act, they “invite” them. From a Jewish perspective, Paul was born into the Abrahamic covenant which already placed significant obligations on him to serve God. Paul accepted his invitation to serve and was able to effectively preach the gospel. Having been born in the covenant he was expected to serve God but once he accepted the invitation he was doubly-obligated to serve God. Acknowledging the nuances of charis means that we should not focus only on the offer, but also view Paul’s service as part of the message. Both God and Paul acted.

Galatians 2:9 shows that the “pillars of the church” (Peter, James, and John) approved Paul’s ministry because they saw he had received a full measure of God’s gift of grace (“perceived the grace that was given unto me”). They saw that Paul had received the truth and was teaching it, and he had the power of God with him. They welcomed Paul as a disciple and gave him the right hand of fellowship.[8] The right hand of fellowship and the assignment to go on a mission may be a signal that Paul had entered into a covenant. Paul first became converted and was baptized, and then became an effective missionary.

In Philippians 1:7–9, Paul states, “It is right for me to be thus minded on behalf of you all, because I have you in my heart, inasmuch as, both in my bonds and in the defence and confirmation of the gospel, ye all are partakers with me of grace. For God is my witness, how I long after you all in the tender mercies of Christ Jesus. And this I pray, that your love may abound yet more and more in knowledge and all discernment” (English Revised Version). Paul states that he has others’ best interest in his heart through his labors and sufferings as he served them. Because he had served them and they belonged to the Christian community, he invited them to appropriately reciprocate by developing more love, knowledge, and judgment. Matthew Henry’s commentary agrees that grace here indicates how much Paul loved the Philippians because he had served them and they had “joined with [him] in doing and suffering. . . . He loved them because they adhered to him in his bonds.”[9] Service and reciprocal response brought unity.

Converted Communities Entered Charis Relationships

In Ephesians 1:5–6, Paul taught that in God’s plan, disciples can truly become children of Christ. “Having predestinated us unto the adoption of children by Jesus Christ to himself, according to the good pleasure of his will, To the praise of the glory of his grace [charitos], wherein he hath made us accepted [echaritosen] in the beloved,” is the text according to the KJV. Echaritosen might be translated as “he has given with grace.” Other translations define echaritosen as grace freely given: “To the praise of his glorious grace, which he has freely given us in the One he loves” (NIV) and “To the praise of the glory of His grace, which He freely bestowed on us in the Beloved” (New American Standard Bible). These versions add the idea of grace freely given to the Greek word echaritosen, but “freely” is not clearly present in the Greek. The Interpreter’s Bible notes, “The verb echaritosen (freely bestowed) is formed on the stem of the noun charis (grace), as if to mean ‘the grace that grace has given.’ It is as if the writer were so enraptured with the word that he can hardly bear to let it go; he is absorbed in the thought that God’s grace overflows in grace to us, lavishes grace upon us.”[10] But Paul’s point is that covenants with Christ bring people to him in obligated relationships. This was the social norm in the Mediterranean world and expected according to ancient conventions associated with charis and what Paul seems to have meant. Paul continues (Eph. 1:7), “In him we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of sins, in accordance with the riches of God’s grace [charitos],” emphasizing aspects of grace, but never denying the need for covenant.

In 2 Corinthians chapters 8 and 9, Paul reflects on the many facets of the effort to provide relief to the saints in Jerusalem, an effort that formed a three-way reciprocal relationship among the Pauline communities, the saints in Jerusalem, and God.[11] Paul teaches about grace and thanks the Corinthians for giving charis gifts to the saints at Jerusalem. The principle Paul teaches here is that those who sow (or give) sparingly will reap (or receive) sparingly, and those who sow bountifully will reap bountifully. Sowing and reaping are reciprocal (2 Cor. 9:6). And just as God gives grace, his disciples receive and are expected to do good works themselves and build communities (2 Cor. 9:8). The Jerusalem members were genuinely and appropriately grateful for the Corinthians’ charis gift to them by being concerned for the Corinthians’ well-being and praying that the Corinthians would receive an overabundance of grace (charin) from God in return for their gifts. Paul also expressed hope that the Corinthians would eventually be blessed by more gifts of God because they had given the Jerusalem community a gift. The Corinthians’ charitable acts toward those in Jerusalem are a manifestation of their charis to God.

Likewise, in Colossians 1, Paul commends the Christian community at Colosse because they not only have faith in Jesus, they also have love for all the saints (Col. 1:4). Their love for other saints resulted from them hearing the gospel and accepting “the grace of God in truth” (Col. 1:6). Because of their entering into that charis relationship, Paul and others did “not cease to pray for [them],” and desired that the Colossians would “be filled with the knowledge of his will in all wisdom and spiritual understanding, That ye might walk worthy of the Lord unto all pleasing, being fruitful in every good work, and increasing in the knowledge of God.” These expressions evoke several meanings of charis: pleasing, fruitful (or rewarding), and accepting the will of the giver (God).

Paul Invites His Readers to Act Properly through Charis

Paul informed his readers that the righteous must teach correct doctrine (logos) so that this doctrine would provide the gift of grace for those listening: “Let no corrupt communication proceed out of your mouth, but that which is good to the use of edifying, that it may minister grace unto the hearers” (Eph. 4:29). For Paul, only by speaking correct doctrine could a disciple offer hearers a chance to enter into and maintain a charis relationship with God.

Gospel discussions should always center on the grace or gift of Christ, as Paul teaches in Colossians 4:6: “Let your speech be always with grace, seasoned with salt, that ye may know how ye ought to answer every man.” Gracious, pleasant conversation should be “seasoned with salt,” which in Greek usage meant to be enlivened with wisdom.[12] If disciples would base their conversation and oration in God’s grace and in wisdom, they would be able to answer every man’s questions and complaints.

Paul’s Reciprocal Relationships of Guardian/Prisoner and Master/Slave

Paul utilized the motif of “prisoner” (2 Tim. 1:8; Eph. 3:1; 4:1) of Jesus Christ to express his dependence on God as guardian in a patron-client relationship informed by charis. In the ancient worldview, this dependent relationship meant that Paul would receive God’s continued blessings of protection. In the beginning of three of Paul’s epistles (namely Rom. 1:1; Philip. 1:1; Titus 1:1) and in Galatians 1:10, Paul referred to himself as a “slave” of God (douloi, “slave” in numerous versions; “servant” in KJV) to reflect that he was bound by covenant to do God’s will. Peter and James also used the term doulos to depict themselves as slaves as a means of teaching that disciples should cultivate reciprocal relationships (2 Pet. 1:1; James 1:1). In belonging to a master/slave relationship, they placed themselves in care of the master, who could eventually free them from death and sin.

As demonstrated in the previous chapter, asymmetrical social relationships between patron and client and between master and slave were founded on the reciprocal notion of charis. It should be noted that ancient slavery was not based on race. The low class of slaves labored with their hands and were considered tools, as if they were underdeveloped mentally, in contrast to educated slaves who were physicians, scribes, or, rarely, assistants to Roman emperors.[13] Ancient Gentiles held prejudices against manual labor because it was associated with moral corruption, vice, and slavery.[14]

Roman slaves in time gained their freedom through good service and the Roman institution of peculium (the slaves keeping a portion of the money they earned for the master).[15] This would be the expectation of most first-century slaves throughout the Mediterranean. The apostles used the slave/servant concept to explain that by keeping their covenant with their master, they would in time be rewarded, but they viewed their covenant as permanent.

The book of Philemon is Paul’s letter to Philemon, a slave owner and probably a wealthy church leader in Colosse. Paul asks, and in fact insists, that Philemon welcome back his former (possibly runaway) slave, Onesimus, as a fellow Christian and social equal. Paul’s intervention placed Onesimus in debt to Paul.[16] This slave was expected to reciprocate and remained “pitiably in even greater debt to Paul, the gracious giver. Even by doing what Paul asks and by providing hospitality, he will never catch up and attain parity with Paul, and this is the whole point.”[17] Paul’s desire to grant charis to the slave is a type of the charis that Paul taught should exist between mankind as disciple-slave and Christ the master.

Grace Empowers

Paul taught that grace goes hand in hand with the power of God to do his will. Grace is manifested in the apostles’ powerful actions, speeches, and letters, in the gifts of the spirit that Christians were given, and through the Holy Ghost. The apostles spoke “with great power” about the resurrection, and “God’s grace was so powerfully at work in them all” that there were no poor among the converts (Acts 4:33–34, NIV). According to Luke, Paul and Barnabas were entrusted with grace because of the righteous “work which they fulfilled” (Acts 14:26). Paul was trusted by the brethren when he left with Silas because of the effective missionary labors he had been engaged in (Acts 14:40).

Paul writes in his epistles that the gift of God’s grace grants power and that all the diverse spiritual gifts (or powers) are received through grace: “We have different gifts, according to the grace given to each of us. If your gift is prophesying, then prophesy in accordance with your faith” (Rom. 12:6, NIV). In this chapter Paul associates charis with the gifts of prophesying, serving, teaching, encouraging, giving, leading, and showing mercy. Anyone who accepted and used these gifts showed God that he was grateful for the gift and had faith in God. When the recipient accepted the gift, he accepted the obligation to use this power to bless others. Paul’s teaching about charis is solidly within the meaning it had for the Greeks.

Paul in the role of an apostle received the power of boldness because of the gift of God’s grace: “Nevertheless, brethren, I have written the more boldly unto you in some sort, as putting you in mind, because of the grace that is given to me of God” (Rom. 15:15). Paul expressed that he was motivated to write boldly because of the charis relationship God had given him.

Paul credits grace as a means of empowerment in several places in his epistles. Paul claimed that because of the gift of grace he was able to be “a wise masterbuilder,” so in turn he fulfilled his obligation by laying a foundation for Christ (1 Cor. 3:10–11). Because of the grace of God he had a “testimony of conscience” that empowered him in simplicity and godly sincerity (2 Cor. 1:12). Paul wrote that the Lord had told him that his grace was sufficient. As Paul became humble, his weaknesses became strengths and gave him power; God’s gift could heal the thorn in the flesh, and receiving this gift perfectly in weakness helped him to appreciate human weakness (2 Cor. 12:7–10).[18] “By the grace of God I am what I am: and his grace which was bestowed upon me was not in vain; but I laboured more abundantly than they all: yet not I, but the grace of God which was with me,” he wrote (1 Cor. 15:10). Everywhere, Paul credits his becoming an effective apostle to the gift of grace: he entered into the reciprocal covenant that Christ offered him, and that relationship gave him strength. Grace served Paul as an anchor, and he taught others to let their hearts be strengthened by grace and not be carried away by false practice (Heb. 13:9). Paul always credits Christ: by the effectual working of Christ’s power, God gave Paul the gift of grace: “I was made a minister, according to the gift of grace of God given unto me by the effectual working of his power. Unto me, who am less than the least of all saints, is this grace given, that I should preach among the Gentiles the unsearchable riches of Christ” (Eph. 3:7–8).

The power to repent, change, and obtain forgiveness comes through reciprocal grace. In his first epistle to Timothy, Paul explained that God’s charis provides a way for sinners to repent and enter Christ’s covenant. Then he told that he had been a blasphemer and persecutor, but he obtained mercy. Grace and mercy applied to him personally. He was a true teacher because “the grace of our Lord was exceeding abundant with faith and love which is in Christ Jesus” (1 Tim. 1:14).

Grace as Victory over Physical Death and the Possibility of Victory over Spiritual Death

Paul credits grace for the means by which Christ performed the Atonement: “he suffered death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone” (Heb. 2:9, NIV). Being empowered through receiving and keeping his covenant with the Father, Jesus was able to overcome physical death. Hebrews and Greeks and everyone else will be saved from death through the grace of Christ. Salvation from physical death (the resurrection) was the good news of the gospel, especially for the Roman Gentiles who typically believed that they ceased to exist after death.[19]

Paul clearly taught that Christ’s grace overcomes physical death through the resurrection—a doctrine that the Greco-Roman world, as exemplified by the city of Athens, rejected (Acts 17). Paul explains, “(14) Death reigned from the time of Adam to the time of Moses, even over those who did not sin by breaking a command, as did Adam, who is a pattern of the one to come. (15) But the gift [of Christ, charisma] is not like the trespass [of Adam]. For if the many died by the trespass of the one man [Adam], how much more did God’s grace and the gift that came by the grace [charis] of the one man, Jesus Christ, overflow to the many! (16) Nor can the gift of God be compared with the result of one man’s sin: The judgment followed one sin and brought condemnation, but the gift [charisma] followed many trespasses and brought justification. (17) For if, by the trespass of the one man, death reigned through that one man, how much more will those who receive God’s abundant provision of grace and of the gift of righteousness reign in life through the one man, Jesus Christ” (Rom. 5:14–17, NIV). The term charisma, which Paul uses to describe the divine gift of resurrection, describes Christ’s power over physical death. This is a vicarious gift of one to help the many. All will gain immortality. The gift is free in the sense that all who have lived on the earth, regardless of how they lived, will eventually receive it. However, verse 17 deals with another subject: spiritual death, or eternal separation from God. By including the condition “those who receive God’s abundant provision of grace and of the gift of righteousness reign in life,” Paul clarifies that this gift is not received by all people. It is offered to all, but some reject it. This is the gift of spiritual resurrection, or what Latter-day Saint doctrine calls “exaltation” or “eternal life,” life in the presence of God. Paul calls this charis gift “abundant” grace. This plan of salvation from physical and spiritual death was based on the law of sacrifice, specifically the gift of Christ’s sacrifice, which was well known before the world existed (2 Tim. 1:9).

Paul elsewhere affirms that there are two kinds of salvation: physical salvation given to everyone, and spiritual salvation given only to those who come to Christ, obey his word, repent, and become clean through the Atonement. In Romans 11:5–6, Paul explained that in his day as in the days of Elijah (a time when many Jews worshipped idols), a remnant of the Lord’s chosen people had been preserved. Some Jews would accept Christ and be saved through him. When Paul says in Romans 11:6 (consistently using the word charis), “And if by grace, then is it no more of works: otherwise grace is no more grace. But if it be of works, then it is no more grace: otherwise work is no more work,” I believe he means that the Jews (a remnant) who accepted Christ would be preserved and saved through him and not through conformity to Jewish law.[20] Paul establishes that only by coming to Christ can the Jews be saved from spiritual death. While Paul does not here explain that coming to Christ meant accepting Christ’s new law, with higher commandments such as Matthew 5–7 and throughout the Gospels, I believe it is understood in the context of charis that discipleship includes specific requirements such as faith, baptism, and good works. Romans 11:6 is often taken to mean that grace has nothing to do with works and thus there is nothing men can do to earn salvation. But I think Paul’s point is that God has not abandoned the Jews; God wants the Jews to focus on Christ and not on their old law. I would add that Paul stresses that converts must appreciate God’s favor; this verse is not to be taken as a definition of grace that renounces acts or covenants.

I agree with Adam Miller’s reading of Romans 11:7–10: “This means that some of God’s insiders[21] have found what they were looking for. Some of them have found grace. The rest, though, were hardened. And of them, many have said: Bereft, they grew listless and dull. They couldn’t see with their eyes. They couldn’t hear with their ears. They couldn’t get up from the couch. They continue lifeless to the present day.”[22] Implicit here is that spiritual salvation depends on choices and actions.

In Ephesians 4:7, each person is “given grace according to the measure of the gift of Christ,” hinting that some who have lived upon the earth will not receive the full benefits of the gift of Christ’s Atonement. People follow God to different degrees, make covenants and keep them to different degrees, and will one day receive a degree of glory (1 Cor. 15:40–42). If disciples do not keep their covenants implied by grace, these covenants made with God will have no effect. Keeping covenants is essential to overcome spiritual death and receive exaltation (2 Cor. 6:1). Those who fall from grace by not completely accepting the Savior will not gain exaltation (Gal. 5:4). The Savior grants forgiveness of sins to make it possible for his disciples to return to live with God (Eph. 1:7). His disciples will understand his kind grace through the ages to come (Eph. 2:7) and will have everlasting consolation therein (2 Thes. 2:16).

Here I feel that a brief discussion about the difference between physical death and spiritual death from an LDS point of view is in order. The doctrine of the LDS Church specifies a distinction between immortality and eternal life: “General salvation comes regardless of obedience to gospel principles or laws and results solely in resurrection from the dead. In this respect, salvation is synonymous with immortality, in that the resurrected person will live forever. Resurrection comes to every person born into this world through the sacrifice made by Jesus Christ, whether one confesses Christ or not. . . . Exaltation [immortality in the presence of God, or overcoming spiritual death] comes as a gift from God, dependent upon my obedience to God’s law.”[23] This statement clearly shows that exaltation is a gift (a grace, a favor) that is obtained only upon condition of obedience.

Grace as a Greeting and Wish for Converts

Greeks commonly used the word chairein, related to charis and meaning “joy to you,” as a greeting at the beginning or end of letters. Duvall and Hays explain, “Paul and Peter both replaced chairein with the word charis (‘grace’) and added the normal Jewish greeting ‘peace.’ In this way they completely transformed the standard greeting and filled it with Christian meaning. ‘Grace and peace to you’ is a greeting, but it is also a prayer.”[24] Paul’s primary concern as an apostle was to make sure that all of his converts personally received the full benefits of the gift of Christ’s atoning sacrifice. Almost half of Paul’s uses of the word charis are found with expressions of his hopes that others receive grace. In 1 Timothy 6:21, Paul’s statement of hope that grace be with the converts follows much admonition regarding Christian behavior. At other times he states his desire to make grace known to individuals as is found in 2 Corinthians 8:1. Paul uses the term charis in Galatians 1:6 (“I marvel that ye are so soon removed from him that called you into the grace of Christ unto another gospel,” NIV), followed by the phrase of Christ to demonstrate his concern that church members were moving away from the gospel: not just any charis, but Christ’s charis. Paul intended to invoke the transformative effects of grace. Judith Lieu writes that by using the term charis in these greetings, Paul does “emphasize religious content and give the greeting more than conventional force.”[25] It seems that Paul hoped fellow Christians would wholeheartedly receive the joy that comes from accepting the full benefits of the Savior’s Atonement. Through his prayers, Paul exhorted his fellow Christians to receive the full benefits of the gift of the Atonement by keeping God’s commandments and enduring to the end. Thus Paul uses charis both as an appeal that people would reciprocate his good actions and as a reminder about the gift of the Atonement of Jesus Christ, encouraging these early Saints to take the necessary steps that would lead them on the path toward eternal life.

Faith, Thanksgiving, and Fulfilling the Law as Part of Grace

Many more examples of Paul using charis to include reciprocity abound in his works. Paul taught in Romans 5:2 that to gain access to grace, one must have faith. In addition, Paul noted in Romans 6:1–4 that baptized disciples cannot continue in sin with grace because the obligatory covenant of baptism has already been made. He counseled the Corinthians that they should not “receive the grace of God in vain,” since it implies obligations and good works (2 Cor. 6:1). Paul hoped that the Thessalonians would glorify Jesus’ name according to grace (charin; 2 Thes. 1:2). In Hebrews 4:16, Paul taught that all must “come . . . to the throne of grace” to find “help in time of need.” Reciprocal connotations of obligatory charis throughout Paul’s epistles are easy to find. These verses provide additional evidence that Paul’s writings on grace were firmly based in the first-century AD milieu in which he wrote, toiled, ministered, and preached.

Thanksgiving was an essential element which often accompanied the obligatory nature of grace. Gratitude permeates Paul’s writings. We must “give thanks [eucharisteite] in all circumstances” (1 Thes. 5:18) and must “be thankful” (Col. 3:15). For covenant people, righteous living is the only appropriate way to respond to the grace of God (2 Cor. 6:1). First Corinthians 1 and 2 Corinthians 8–9 demonstrate proper ancient obligations of thanksgiving to the Lord for his grace.[26] Gratitude and love for God also requires loving one’s neighbor. This same gratitude will help us form a relationship with God as mentioned in 1 Corinthians 1:9 and Colossians 2:7.

Those who keep their covenants demonstrate gratitude to God. Paul taught that to show thankfulness, disciples must consecrate their lives to the Savior in an appropriate manner.[27] Those who have tasted the heavenly gift of grace but produce thorns and thistles instead of fruit represent living a worldly life instead of a Christ-centered one and are close to being cursed and burned (Heb. 6:4–8). Certainly disciples should not slack in the requisite gift of love until they have attempted to show charity for charity—a gift of the spirit that is derived from the roots of charis. This charity is a work that is associated with receiving the full benefits of the Atonement.

In Romans 12 and 1 Thessalonians 5:18, Paul mentions that disciples of the Lord need to make a “living sacrifice.” This living sacrifice was to live a higher law taught by the Savior, for example in the Sermon on the Mount, which replaced animal sacrifice of the law of Moses. The sacrifice of a broken spirit and contrite heart found in Psalm 51:16–17 at last took the place of animal sacrifice.

The Obligations of Participation with the Community

In 2 Corinthians 8:1–6, Paul described in detail this chain of religious obligations of charis for the Macedonians to perform in behalf of God, Christ, Paul, and Jerusalem.[28] The chiastic structure of 2 Corinthians 8:13–15 exhibits reciprocity of charitable obligations in the early Christian relationship between Corinth and Jerusalem.[29] Later in 2 Corinthians 9, the two-way relationship between Jerusalem and Corinth becomes a triangular one that includes God because of active Christian charis.[30] Paul even utilized the reciprocal notion of charis to bless the Saints scattered throughout the Mediterranean.

First Corinthians 9:11 indicates what Paul expects in return for the gifts he has given. He gives converts a precious knowledge of Jesus, and in return asks merely for material gifts. He asks, “If we have sown unto you spiritual things, is it a great thing if we shall reap your carnal things?” Galatians 6:6 outlines the duty of Christians to share: once they have received the gift of the word of Christ, they have a duty to “share all good things with their instructor” (NIV).

Themes of Reciprocity

Ideals of reciprocity coupled with indebtedness appear frequently in Paul’s writings. There are dozens of examples of traditional Greco-Roman forms of grace in Paul’s writings and in other writings later attributed to Paul in which he does not use the word charis but uses socially related terms. For example: “We have spoken freely to you, Corinthians, and opened wide our hearts to you. We are not withholding our affection from you, but you are withholding yours from us. As a fair exchange [antimisthian, recompense]—I speak as to my children—open wide your hearts also” (2 Cor. 6:11–13, NIV). “Owe no man any thing, but to love [agapē] one another: for he that loveth another hath fulfilled the law” (Rom. 13:8).

In Philippians 4:10, Paul seems to have received the Philippians’ special care. In 4:15, he compliments the saints at Philippi for their gifts to him in support of his missionary work: “No church communicated with me as concerning giving and receiving, but ye only.” Paul fulfilled charis when he expressed gratitude for the things sent to him “again unto my necessity” (Philip. 4:16). In 4:19, he acknowledges that he cannot reciprocate directly because he is in prison, and he assures his friends in Philippi that his God will do so for him: “My God will supply all your need.” Paul trusts God’s charis covenant.

In Romans 15, Paul elevated the Greek concept of charis from a secular obligation to an ecclesiastical one: “For Macedonia and Achaia were pleased to make a contribution for the poor among the Lord’s people in Jerusalem. They were pleased to do it, and indeed they owe it to them [literally, they are debtors, opheiletai, meaning those of Macedonia and Achaia were already indebted to those of Jerusalem]. For if the Gentiles have shared in the Jews’ spiritual blessings, they owe it to the Jews to share with them their material blessings” (Rom. 15:26–27, NIV). Paul says that the converts at Macedonia and Achaia were not only pleased to give donations to the Christians at Jerusalem but in fact owed it to them because the Macedonians and Achaians had been given the gift of the gospel first. Peterman explains that “Paul considers the gospel to be a gift which brings about an obligation of gratitude in the form of a material return” and in Romans 15:26 “confirms our conclusion that Paul has a special relationship with the Philippians as a result of giving and receiving.”[31]

Paul demonstrated reciprocal gratitude to God by caring for his converts as parents care for their children. Like proper Gentile parents who were expected to become the bedrock of their children’s physical existence, education, and general well-being, Paul became a great benefactor to his converts and occasionally received reciprocal blessings from them. As an outstanding missionary he assisted his converts so they could get onto the path to eternal life through the Atonement.[32] Paul seems to have even offered money to them to assist them with their material needs (2 Cor. 11:8). However, as noted above, he seems to have received the Philippians’ special care (Philip. 4:10). In both of these responses Paul followed the typical Jewish and Gentile conventions of grace of his time as he gave and received.[33] First Timothy 5:4 preserves an example, unique within the New Testament writings, of an early church teaching that was very common among the Jews and Gentiles: All persons were required to pay back later in life the many blessings they received from their parents.[34] Paul modeled the appropriate parent/child reciprocal relationship for his converts.

Understanding What Paul Is Really Teaching through Charis

The many passages about charis stress the obligations Christians have. These have often been overlooked as later theologians placed emphasis on the “free” aspects of grace. It is important to try to understand Paul’s teaching as his gentile audience in first century AD would have understood it. I believe Paul’s message has been misinterpreted and distorted by Augustine, Martin Luther, and others, as later chapters will explain.

The oft-cited Romans 3:24 might be used to contradict the thesis of this work. The King James Version reads, “Being justified freely [dorean] by his grace through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus.” However, dorean means “as a gift,” not freely. Gifts were not given “freely” in the ancient Mediterranean world because every gift had nuances of reciprocity. In his translation, Joseph Smith rightly changes the word freely to only (“Therefore being justified only by his grace . . .”), reflecting the absolute power of the Atonement.[35] In addition to Romans 3:24, the KJV translators rendered the word charis in Romans 5:15–16, 18, as “the free gift.” In his epistle to the Romans, Paul needed to argue for a reciprocal gift of physical and spiritual salvation from the Savior because both Greeks and Romans did not generally understand or accept life after death, resurrection, and eternal life. The first-century philosophies of the day—cynicism, Epicureanism, stoicism, and neo-Platonism—taught divergent and very abstract views on death and the afterlife (or lack of one). Gentiles did not usually accept the doctrine of a physical resurrection or spiritual salvation, necessitating Paul’s frequent treatment of this subject in his epistles, especially to the Romans.[36]

In his Epistle to the Romans, Paul sometimes discusses salvation ambiguously but at times refers specifically to salvation from physical and spiritual death. Romans chapter 6 is an example of Paul’s teaching regarding the doctrine of being saved from both physical and spiritual death through the Atonement. Paul alternates his teaching in this passage by switching back and forth between two related but distinct concepts of salvation: overcoming physical death and overcoming spiritual death. Romans 6:1–4 discusses not continuing in sin (overcoming spiritual death through obedience). Verse 5 explains that all will be resurrected (overcoming physical death). In verses 6–8 Paul teaches that disciples are freed from sin through Christ (with Christ, a person can overcome spiritual death). Verse 9 deals with the permanence of Christ’s resurrection (overcoming physical death). Verses 10–23 explain the theme of avoiding sin through being empowered by Christ’s grace (overcoming spiritual death). All will eventually be physically resurrected, but Paul further discusses the doctrines of the gospel which become the means by which his converts may avoid spiritual death.

Because some Christians today do not make the theological distinction between physical and spiritual death, some assume that all will be saved.[37] Many Christians consider a literal, physical resurrection problematic because of anti-materialistic, philosophical notions first taught by Greek philosophers and then adopted by Church fathers who argued for a mystical and only spiritual resurrection.[38] Many traditions follow the fourth-century theologian Athanasius, who argued for some kind of mysterious, nonphysical but spiritual unification with God.[39] Therefore, this form of grace is now associated with deliverance from spiritual death without a literal, physical resurrection. Finally, the ancient convention of reciprocal charis and its obligations is compatible with a material, object-oriented universe.[40]

Perhaps one might argue that Paul overturned reciprocal ideals of grace in his writings. If one looks at the ideas of grace in Romans specifically, which was almost certainly written by Paul, one might find it therefore necessary to reinterpret how he uses grace in writings that were only attributed to him. This theory that Paul taught a new meaning for the word charis is problematic for many reasons. Some Protestant theologians have commonly employed a few select Pauline passages to interpret others.[41] After interpreting Paul’s meaning of charis as a free, permanent, no-obligation gift from God, they reinterpret the entire Bible to argue that Paul, in fact, invented a new version of Christianity that his Gentile converts understood and accepted.

Another modern notion associated with free grace in Christendom is that a person does not have to do anything to be saved except confess and believe: “That if thou shalt confess with thy mouth the Lord Jesus, and shalt believe in thine heart that God hath raised him from the dead, thou shalt be saved” (Rom. 10:9). This verse has come to mean for some Christians that a person who makes a one-time confession and continues to believe will be saved.[42] However, Romans 10:9 does not have the covenantal nuances in the KJV that it probably had in the first century AD. The word that is translated as “confess” is the verb homologeō. In classical Greek, meanings of this word range from “to confess, admit, acknowledge, assent, and to agree.”[43] Beginning as early as the Egyptians, saying a god’s name was very serious because it would give one power over that deity.[44] Names of deities were often used in ritual fashion to gain power over them and the various names of God, including Jehovah, are mentioned together with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob throughout the Old Testament to emphasize Israel’s covenant. An educated, bilingual Roman of the first century AD would have probably understood Paul’s Greek phrase in Romans 10:9 to mean (my translation): “If you vocally assent to the covenantal phrase that Jesus is Jehovah and you have confidence in your heart in Jesus’ physical resurrection, you will be made spiritually well.”[45] Paul is affirming the basics of the plan of salvation with its accompanying covenants and encouraging converts to transform their lives and become true disciples. A sincere testimony demonstrates gratitude for the gift of the Atonement according to the nuances of charis. This passage in Romans does not justify an “easy” form of grace devoid of any obligations.

It is necessary to analyze charis according to its ancient setting to evaluate this conventional argument. James Harrison argued that Paul in Galatians 2:14–15 overturned some conventions of Greco-Roman reciprocity. Harrison believed that certain Christian benefactors “had gone beyond the normal bounds of generosity.”[46] Furthermore, Harrison claimed that in serving and loving in Luke 6:27–38; 14:12–14; 22:24–27, Jesus expected his disciples to go beyond the Hellenistic reciprocity and honor systems.[47] Certainly some of Jesus’ teachings involve other gospel principles including agapē, charity, and not just charis. In the conclusion of his work, Harrison seems to defend the traditional Protestant doctrine of free grace by hinting that Jesus and Paul rejected some aspects of Greco-Roman charis while still wisely cautioning the Protestant reader that Paul’s ideas about charis could not have been far outside of the first century AD system of reciprocity. Harrison clearly admits that it is unlikely that Jesus and Paul would have taught a new version of charis when he states, “We must resist the temptation to overstate our case at this juncture.”[48]

In contrast, another scholar, Klyne Snodgrass, determined that a few passages of Paul have been misunderstood so that they belie Paul’s central message of keeping God’s commandments. Snodgrass argues that New Testament commentaries become very brief, evasive, and obtuse in the treatment of Romans 2 and try to explain away the text that emphasizes the necessity of good works, especially verse 13: “The doers of the law will be justified.” They generally argue that Paul must be speaking only hypothetically because commentators argue that what really Paul believes is found in Romans 3:9 and 3:20. Snodgrass writes, “To argue that Paul did not accept the statements in 2.6–16 not only sets him at odds with Judaism, the Old Testament, Jesus, the rest of Christianity and indeed, himself, but makes difficult any thought of seeing Romans in light of his intended trip to Jerusalem. Paul’s defense of his mission would not have had the slightest chance with Jews or Jewish Christians had he rejected this cardinal belief of the biblical and Jewish tradition.”[49]

What is Paul teaching about grace in Romans? How should Latter-day Saints interpret grace as a whole in Paul’s writings? Before analyzing the meaning of charis in Paul’s work, we must be clear what we mean by “salvation.” The restored gospel of Jesus Christ makes the critical distinction between the resurrection, or salvation from physical death, and exaltation, or spiritual salvation. Scriptures of the restoration clearly teach that all will be resurrected (although at different times depending on their faithfulness) and receive a kingdom of glory.[50] Through the Atonement and the Resurrection, the Savior overcame physical death, and everyone will be resurrected. But to overcome spiritual death (to return to live with God and be exalted) we must be valiant in our testimonies of the Savior and keep his commandments until the end of our lives (D&C 76:79). In the next life we will be reciprocally rewarded to the degree we are valiant, receive a fullness of Christ’s grace, and make and keep covenants.

Many Christians do not believe in a physical resurrection, but, like Augustine, believe that having a physical body is crass compared to existing as a spirit.[51] However, Latter-day Saints know through modern revelation that we will receive an immortal, perfect body of flesh and bone—not a mundane earthly one. The doctrine of salvation is so important for God’s children that these questions must be asked and answered. Only through understanding the difference between salvation from physical and from spiritual death in his epistles do Paul’s writings become lucid.

The second doctrinal issue that should be noted, with which many Protestants may be uncomfortable, is that covenants reflecting reciprocal grace were important in both Jewish and Gentile (Greco-Roman) traditions. Surely the covenant of the Mosaic Law is different than the New Covenant established by Christ and restored again by Christ through the Prophet Joseph Smith. But the covenantal relationship between God and his people still exists. In fact, the name “New Testament” should more accurately be “New Covenant.”[52] Bernard Jackson concludes that “the theological development of the covenant concept may now be derived from studies of the Greco-Roman background of charis (grace). . . . In the Hebrew Bible, covenant is associated in some sources with hesed, variously translated lovingkindness or mercy: God is said to keep the covenant and show mercy. Such ‘covenant love’ ‘always has strong elements of reciprocity in its usage.’ . . . charis is not to be taken in the later Christian sense.”[53]

Many groups in Christendom beginning with the early Church fathers rejected the notion of covenants because they associated them with the earlier law of Moses. They seem to have also despised rituals that are a vehicle to making covenants because of later Greek philosophy.[54] By linking charis with covenants with God, even in light of the fact that the law of Moses was now fulfilled, Paul taught the Gentiles how to overcome the effects of spiritual death. Paul states that as a covenantal benefactor (Rom. 5), Heavenly Father offered his Only Begotten Son as a ransom payment (Rom. 3:24). Jesus became a blood sacrifice to fulfill the demands of the laws both of justice and of mercy for both Jew and Gentile (Rom. 3:25, 29–30) because of a covenant of the Atonement (Rom. 3:26). Finally Jesus was resurrected (Rom. 6:4; Philip. 2:11; 2 Cor. 2:8).[55]

Through the Atonement of the Savior, all people are able to make covenants that imply reciprocity, coupled with love for Heavenly Father and others. Like the ancient convention of asymmetrical reciprocity, the covenants that people make today through ordinances are contracted with God alone. Miroslav Volf notes the importance of making covenants with God as part of charity for others: “Untethered from God, self-giving love cannot stand on its own for long. If it excludes God, it will destroy us, for we will then deliver ourselves to the mercy of the finite, and therefore inherently unreliable, objects of our love. The only way to ensure that we will not lose our very selves if we give ourselves to others is if our love for the other passes first through God.”[56] He argues that Jesus’ new covenant of charis made agapē possible. Baruch Levine adds that the golden rule in Leviticus 19:18 and in the New Testament (Matt. 7:12) are based on ancient notions of reciprocity.[57] By means of reciprocal covenants with God, a convert is enabled to develop love or agapē for God and others (Matt. 22:37).

Because of this charis relationship established through covenants, disciples are always obligated to keep all of his commandments given through his Son, Jesus Christ. Those who develop the spiritual gift of charity reciprocate thankfulness to God. When disciples keep their covenants, God is reciprocally bound to grant his promised blessings. Having charity for others it is not a sign that one has gone beyond the expectations of a freely granted charis in the modern sense. Rather, it is a result of the covenants one has made with God to love all of his children.[58] Conversely, a lack of charity is a sin against God because God expects his children to show concern for others. Certainly following all of Jesus’ commandments in his New Covenant goes far beyond the typical Greco-Roman reciprocity between individuals because it requires loving one’s enemies, going the extra mile, and always forgiving others. The spiritual gift of agapē can be lived once covenants are made and kept. But we must remember that the ancient religious concept of charis was often formed between the gods and mankind. As the Savior’s disciples develop the gift of charity they fulfill their obligations of reciprocity to Heavenly Father alone—not to man.

Therefore, in respectful disagreement with Harrison on this point, Jesus or Paul did not, in fact, go beyond the normal bounds of reciprocity within the ancient world. Jesus and Paul emphasized religious forms of reciprocity by loving God through keeping covenants. Because disciples willingly make these covenants with Heavenly Father through his Son and not with anyone else, they must keep Jesus’ commandments of this New Covenant according to God’s standards. Paul’s message about charis in the new context of Christ’s gospel includes the connotations of obligations, reciprocity, keeping God’s commandments, and making covenants. This is how Paul and his message of reciprocal grace were understood by his first-century converts.

Thus the ancient concept of obligatory and reciprocal grace as affirmed by Christ’s New Covenant is still in force in the New Testament. When disciples make a choice to serve others, they are acting in accordance with covenants, made and kept in a reciprocal manner with God. They are under religious obligations to others because they are commanded to first love God and then their neighbor. The Book of Mormon beautifully explains that when people serve others, they are only serving God (Mosiah 2:17). Those who keep covenants with God share in God’s work and glory, which is “to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man” (Moses 1:39).

[1]. Seth Schwartz, Were the Jews a Mediterranean Society? Reciprocity and Solidarity in Ancient Judaism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 15, 169.

[2]. Paul had a multicultural background as a Jew, Roman, and Greek. He looked forward to a Messiah and recognized Jesus as the Messiah (see Gal. 3:24, where Paul speaks of Jewish law as a guardian until the coming of the christon, which in some versions is translated as Messiah). He lived in the Greco-Roman world, wrote in Greek, and was a Roman citizen. On Paul’s background, see Stanley E. Porter, ed., Paul: Jew, Greek, and Roman (Leiden: Brill, 2008).

[3]. Some of Paul’s writings have been considered by scholars to have definitely been written by Paul, while other writings attributed to him may have been written by his secretary, another apostle, or by other early Christians. New Testament authorship is peripheral to this study. If pseudo-Pauline writings were considered orthodox by very early Christians because of their teachings, then it is likely that they contain doctrines associated with Jesus’ apostles, whether written by Paul or another Christian leader. Also, when examined through the reciprocal nuances of charis, all writings whether attributed or not to Paul emphasize covenants, being obligated to God, and reciprocating love to God and others.

[4]. According to Strong’s Concordance of the Bible, counting “charis” and “charin.” There are other ways to study word usage and word counts in the Bible, but Strong’s is adequate for the purposes of this study. This number counts every use of the word separately, even those that occur more than once in a verse. In addition to the 157 uses of charis as a noun, there are 9 uses of charin, the adjective form.

[5]. The chart was compiled by using resources at Bible Hub, s.v. “5485.χάρις (charis),” http://biblehub.com/greek/strongs_5485.htm, citing Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible and the Interlinear Bible by Biblos.com.

[6]. See for example the previous discussions of Homer, Aristotle, Proculus, and Thucydides.

[7]. The English translation “But when it pleased God” (KJV) was probably added to the Bible much later and is considered doubtful by New Testament scholars. See Bruce Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the New Testament, 3d ed. (London: UBS, 1971), 590.

[8]. Second Peter 3:15 is evidence that Peter accepted Paul as a disciple and missionary.

[9]. Matthew Henry’s Commentary, s.v. Philippians 1:7–8, online at Bible Gateway, https://www.biblegateway.com/resources/matthew-henry/Phil.1.7-Phil.1.8. Matthew Henry wrote a six-volume, verse by verse commentary of the Bible, published in 1708–10, which is still popular today.

[10]. Francis W. Beare, “Ephesians,” in The Interpreter’s Bible, 12 vols. (New York: Abingdon, 1953), 10:617. On the same page, Theodore O. Wedel, writing the exposition, firmly reminds us of God’s exactness and the costliness of grace: for God to forgive us cost the precious blood of Christ. Thus this version sees grace as both free and costly.

[11]. Romans 15:25, 28; quoted in Joubert, Paul as Benefactor, 133. See also Joubert’s discussion on this topic on pp. 139, 140, 200, 202, 216; and Richard R. Melick Jr., “The Collection for the Saints: 2 Corinthians 8–9,” Criswell Theological Review 4, no. 1 (1989): 97–117.

[12]. Salt was also associated with cleansing and preservation, adding more meaning to this exhortation.

[13]. See Aristotle, Politics 1253b–1254a.

[14]. Sallust, Cataline Conspiracy 4, states that a good Roman, such as himself, should spend one’s leisure time in academic pursuits like writing history instead of servile activities like manual farm labor, duties of governance, or pursuing entertainment.

[15]. “Allowing the slave to hold property [or a peculium] provided an incentive for the slave to work hard. . . . Indeed a slave was often allowed to buy his freedom with his or her peculium. And when slaves were freed in their master’s will, it was common for them to receive the peculium by way of a legacy.” Borkowski, Textbook on Roman Law, 94–96, 114–16.

[16]. See the discussion in John K. Chow, Patronage and Power: A Study of Social Networks in Corinth (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1992).

[17]. Osiek, “Politics of Patronage,” 143–52.

[18]. This evokes Moroni’s message in Ether 12.

[19]. For example, the writings of the epicurean philosopher Lucretius’s De Rerum Natura contain these sentiments. De Rerum Natura book 4 says our atoms dissolve into nothingness, signifying that at death we will be obliterated.

[20]. “‘Works’ here mean conformity to the Law.” Barnes’ Notes on the Bible, at Bible Hub, http://biblehub.com/commentaries/romans/11-6.htm.

[21]. “Insiders” is the word Miller uses for the Jews vis-à-vis the Gentiles (outsiders).

[22]. Adam S. Miller, Grace Is Not God’s Backup Plan (Amazon, 2015), 55–56.

[23]. Theodore M. Burton, “Salvation and Exaltation,” Ensign 2 (July 1972): 78–79.

[24]. J. Scott Duvall and J. Daniel Hays, Grasping God’s Word (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2005), 233.

[25]. Judith M. Lieu, “‘Grace to You and Peace’: The Apostolic Calling,” Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 68 (1985): 169.

[26]. Pao, Thanksgiving, 84.

[27]. Second Corinthians 5:14–15; Galatians 2:20; deSilva, Honor, Patronage, 146.

[28]. See Joubert, Paul as Benefactor, summary on p. 139.

[29]. Joubert, Paul as Benefactor, 140: “2 Corinthians 8, 13–15 forms part of the apostle’s efforts to persuade the Corinthians to commit themselves to the collection again. Paul in v. 13bff, as part of a larger section 8, 7–15, . . . explicitly addresses the need for balanced reciprocity in the relationship between Corinth and Jerusalem. He does this by way of the following structure:

All’ ex isotetos

En to nun kairo to humon perisseuma eis to ekeinon hysterema

hina kai to ekeinon perisseuma genetai eis to humon hysterema

hopos genetai isotes.

[But that there might be equality.

At the present time your plenty will supply what they need,

so that in turn their plenty will supply what you need.

The goal is equality (NIV)]

“. . . This chiastic structure . . . highlights one of the basic principles inherent in reciprocal relationships, although wrapped in the terminology of Paul’s theological reflection, namely that both parties should benefit equally from their social interaction.”

[30]. Joubert, Paul as Benefactor, 200; see Joubert’s excellent summary of active grace required of all Christians for the collection on p. 202, and his final conclusion that Paul practiced reciprocal, obligatory charis, and so should we.

[31]. Peterman, Paul’s Gift, 175.

[32]. Philemon 19; 2 Corinthians 6:13; Peterman, Paul’s Gift, 199–200; Harrison, Paul’s Language of Grace, 342.

[33]. Philippians 4.15; Peterman, Paul’s Gift, 8.

[34]. Peterman, Paul’s Gift, 17; see also Romans 5:7.

[35]. JST Romans 3:24.

[36]. Another example of typical gentile unbelief in the resurrection may be found in Acts 17. Other references are scattered throughout the writings of epicurean Roman poets from the first century BC such as Lucretius, Catullus, and Horace.

[37]. See the discussions in Robin A. Parry and Christopher H. Partridge, Universal Salvation? The Current Debate (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2004); and Wayne Morris, Salvation as Praxis: A Practical Theology of Salvation for a Multi-Faith World (New York: Bloomsbury T & T Clark, 2014), 96–98.

[38]. See a detailed treatment of this subject in Stephen H. Webb, Mormon Christianity: What Other Christians Can Learn from the Latter-day Saints (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[39]. See a good discussion in Keith E. Norman, Deification: The Content of Athanasian Soteriology (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 2000). Also see an interpretation of Iamblichus in Hugh Nibley, Temple and Cosmos: Beyond This Ignorant Present, ed. Don E. Norton, vol. 12 of The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient research and Mormon Studies, 1992), 270.

[40]. I would extend the point to include that reciprocal charis is incompatible with the classical theism in traditional Christendom of an immaterial God without parts or passions, but that is a subject for another time. Webb, Mormon Christianity, brilliantly points out many metaphysical advantages of Mormon theology. Adam S. Miller, Speculative Grace (Bronx, N.Y.: Fordham University Press, 2013), demonstrates how grace operates in an object oriented universe.

[41]. See for example the discussion on Klyne Snodgrass below.

[42]. Examples are easy to find. One is Like The Master Ministries, which explains, “If you believe in your heart that Jesus is Lord, you are saved.” Confessing with words but not truly meaning it is not enough; you must actually believe that Jesus is Lord, and that is enough. Like The Master Ministries, Never Thirsty, http://www.neverthirsty.org/pp/corner/read/r00048.html.

[43]. Online Liddell-Scott-Jones Greek-English Lexicon, s.v. “ὁμολογέω,” http://stephanus.tlg.uci.edu/lsj/#eid=76103&context=search.

[44]. Loren Graham, “The Power of Names: In Culture and in Mathematics,” American Philosophical Society 157 (June 2013): 230, available at http://www.amphilsoc.org/sites/default/files/proceedings/1570204Graham.pdf (accessed 5 July 2015).

[45]. For kyrios meaning Yahweh, see LXX Gen. 11:5 and Online Liddell-Scott-Jones Greek-English Lexicon, s.v. “κύριος,” definitions III.B.3–4, http://stephanus.tlg.uci.edu/lsj/#eid=3948&context=search. The Muslim shahada may be a parallel. Part of the conversion to Islam includes public vocal witness that “There is no god but God, and Muḥammad is the Messenger of God.” Encyclopaedia of Islam, ed. P. Bearman et al. (Leiden: Brill, 2007–), s.v. “Shahada.”

[46]. Harrison, Paul’s Language of Grace, 341.

[47]. Harrison, Paul’s Language of Grace, 352.

[48]. Harrison, Paul’s Language of Grace, 341.

[49]. Klyne R. Snodgrass, “Justification by Grace—to the Doers: An Analysis of the Place of Romans 2 in the Theology of Paul,” New Testament Studies 32 (1986): 86.

[50]. Douglas L. Callister, “Resurrection,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow, 4 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 1222–23; and Alma P. Burton, “Salvation,” in Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 1256–57.

[51]. Terryl L. Givens, Wrestling the Angel: The Foundations of Mormon Thought: Cosmos, God, Humanity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 198 n. 2. Augustine reportedly said, “Intra feces et urinas nominem natus est,” “We are born between urine and feces,” an insult to the birth of humans.

[52]. Bernard S. Jackson, “Why the Name New Testament?” Melilah: Manchester Journal of Jewish Studies 9 (2012): 50–100.

[53]. Jackson, “Why the Name New Testament?” 62. Glueck, Ḥesed in the Bible, makes an argument that covenants and reciprocity obligated Israel after receiving God’s mercy. Glueck argues that Israel was bound by covenant to its deity because of the concept of hesed. Glueck’s thesis has since been widely accepted but its theological implications have generally not been associated with charis. See a discussion on this subject in the Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament, ed. R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer Jr., and Bruce K. Waltke (Chicago: Moody, 1980), 305–7 (entry 398). These editors argue that some Old Testament passages using hesed do not explicitly obligate individuals or groups. However, covenants or other forms of reciprocity seem to always have been implied in these quoted Old Testament texts when understood in the context of ancient reciprocity, anthropology, and sociology.

[54]. Latter-day Saints see this as an apostasy, the changing of key doctrines and loss of authority in the centuries after Christ. In the very Greek sense of apostasia, this apostasy was a revolt against God’s doctrines and authority.

[55]. Harrison, Paul’s Language of Grace, 221, provided some of these insights.

[56]. Miroslav Volf, Free of Charge: Giving and Forgiving in a Culture Stripped of Grace (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2005), 103.

[57]. Baruch A. Levine, “The Golden Rule in Ancient Israelite Scripture,” in Neusner and Chilton, Golden Rule, 11–12.

[58]. Briones, “Mutual Brokers of Grace,” 554, has a diagram in figure 1C illustrating the importance of first making covenants with God.