By Eric D. Huntsman. From Miracles of Jesus, 45–49, and cross-posted at New Testament Thoughts

One of the earliest miracles recorded in the Synoptics is the cleansing of a leper (Mark 1:40–45; Matthew 8:1–4; Luke 5:12–15). Leprosy in the biblical world was not necessarily the better known Hansen’s Disease. Instead, it was a catch-all condition for a spectrum of conditions that affected the skin or even clothing and dwellings (see Leviticus 13:1–59). While some cases may have indeed involved considerable deformity and sickness, every instance of biblical leprosy had significant ritual, and hence social, implications as the sufferer was excluded from religious life and often even the company of others. Hence, the leper who first approached Jesus needed help and attention beyond simply being healed of his disease.

The earliest version of the story preserved by Mark has some textual problems that might raise some questions about how to interpret aspects of the story,[1] but in all three Synoptic accounts it is clear that the leper broke social conventions in his desperate attempt to get help. Regulations governing those suffering from leprosy required that they keep distant from those who were not afflicted, but this man came right up to Jesus and boldly, or perhaps despairingly, entreated him for help, saying, “If thou wilt, thou canst make me clean” (Mark 1:40).[2] Rather than recoiling from the leper, as many of his contemporaries might well have done, Jesus instead compassionately put forth his hand, touched him, and said, “I will; be thou clean” (Mark 1:41). The man was immediately cleansed from his leprosy, and Jesus helped arrange for his social reintegration by directing him to go through the steps mandated by the law of Moses (Mark 1:44; see Leviticus 14:1–32).[3] The prophet Elisha’s help healing Namaan of leprosy is clearly a precedent for Jesus’ act here (2 Kings 5:10–14), but Jesus’ miracle is more direct, more immediate, and, consequently, more powerful.

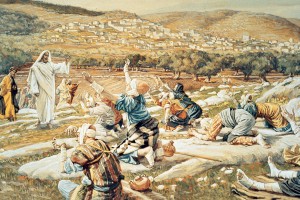

To help stress the superiority of Jesus over Elisha, Luke preserves another account of Jesus healing lepers with the story of ten lepers (Luke 17:11–19). Luke places this miracle later in Jesus’ ministry, when he was on the road to Jerusalem for the final week of his mortal mission. While he was traveling, he encountered 10 lepers, but these men, unlike the first leper healed, “stood afar off,” keeping the conventionally required distance between the unclean and the clean. When these men pled for mercy, Jesus instructed them to show themselves to a priest. While they were traveling, they were miraculously cleansed of their leprosy, making this another instance of Jesus healing at a distance. Of the ten, only one, who happened to be a Samaritan, glorified God and returned to thank Jesus, leading Jesus to commend him. Significantly, when Jesus says, “Arise, go thy way: they faith has made thee whole” (Luke 17:19, emphasis added), the phrase used here for “made thee whole” is sesōken se, which actually means “has saved you.”[4] Pointedly, while all 12 were cleansed (ekatharisthēsan) and healed (iathē) (Luke 17:14–15), only the one who expressed gratitude was “saved.”[5] As one of several instances when a healing of Jesus is described not only in terms of the miraculous cure of a disease but also in the broader terms of salvation, the “saving” of the grateful Samaritan leper suggests a deeper, spiritual healing.

In addition to these specific cases of Jesus curing lepers and making them clean, Jesus mentions this kind of healing when he instructs envoys from John the Baptist to report to the prophet that “The blind receive their sight, and the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, and the deaf hear, the dead are raised up, and the poor have the gospel preached to them” (Matthew 11:5; cf. Luke 7:22). The expression “lepers are cleansed” points to the greater symbolic significance of healing leprosy. None of these lepers are named, allowing the cleansing of lepers to serve as a powerful type of how Jesus makes us clean and pure. Just as biblical leprosy made individuals ritually unclean and unable to join in normal human society, so our fallen state—and especially our willful sins—make us spiritually unclean and unworthy to enter the presence of God (see, for instance, 1 Nephi 10:21; 15:34; Alma 7:21; 11:37; 40:26). In this regard, Luke’s example of the Samaritan leper is of particular importance. Two great miracle-working prophets, Moses and Elisha, both cured leprosy (Numbers 12:13–15; 2 Kings 5:8–14), but Luke’s story provides a most powerful type: our faith in Christ not only makes us clean, it saves us.

[1]Some of these problems include the absence of the participle for “kneeling” (gunypetōn) in many early manuscripts and whether Jesus responded being “moved with compassion” (splangnistheis) or “out of anger” (orgistheis). See Metzger, Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 65, and the discussions of Twelftree, Jesus the Miracle Worker, 62, and Cotter, The Christ of the Miracle Stories, 31–32, 38.

[2]Cotter, The Christ of the Miracle Stories, 29, 33–37.

[3]Demaitre, Leprosy in Premodern Medicine, 234–35.

[4]Radl, “sōzō,” Exegetical Dictionary of the New Testament, 3.320.

[5]Meier, A Marginal Jew, 2.703.