In 2013, Richard Draper and Michael Rhodes published the inaugural volume of the BYU New Testament Commentary series. This was a landmark volume for a landmark series—the most extensive treatment of the book of Revelation by far in a commentary format by Latter-day Saint (LDS) authors for a series that promises to be the most extensive treatment of the New Testament in a commentary series by Latter-day Saint authors. Even more impressive, a significant amount of the scholarship with which Draper and Rhodes interacted came from outside Mormon circles, and of that, the largest percentage came from Evangelical Christian circles. At the same time, the volume was plentifully punctuated by quotations from Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, later LDS Presidents, and other General Authorities over the years. Indeed, each section contained the biblical passage at hand reproduced from the Society of Biblical Literature’s edition of the Greek New Testament, the King James Version (KJV), and a more accurate translation in contemporary English called the BYU Rendition. But no amount of careful translation or scholarship was ever allowed to trump cherished LDS pronouncements by key authorities, and differences in the Joseph Smith Translation (JST) were always noted.

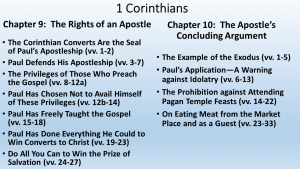

Draper and Rhodes have now collaborated again to produce the volume on 1 Corinthians, utilizing the identical format. In my estimation, it is even better than their very solid and substantial commentary on Revelation. A detailed introduction sets the stage for Paul’s letter by surveying questions of authorship, date, historical background to Corinth, circumstances for writing, unifying themes, and, as a special bonus, a collection of interpretations and famous quotations by LDS authorities for each chapter of the letter, organized in decreasing order of the frequency of comments on the chapter. As is recognized by virtually every recent scholar of any theological perspective who has studied 1 Corinthians in depth, Paul wrote this letter in the mid-50s of the first century to a fledgling church he helped to found against the backdrop of all kinds of cultural challenges that often kept it immature—pagan philosophies, rampant sexual immorality, a port city with all the commerce and merchants coming and going, clashes of widespread multiculturalism, and the pervasive Greco-Roman practice of patronage: the handful of wealthy in the church, as in Greco-Roman society more generally, were wielding an inordinate amount of power over those indebted to them for their financial well-being. This explains a disproportionate number of the problems in Corinth, from factions to lawsuits, from participation in pagan festivals to abuses of the sacraments, and it accounts for why Paul refuses to accept their money for his ministry, even as he argues for the right for full-time workers for the gospel to be paid by their churches.

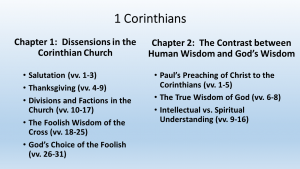

As one begins reading the commentary proper, chapter by chapter and passage by passage through Paul’s letter, one is treated early on to a marvelous excursus on grace, which should warm any Christian’s heart, after Paul’s first use of the term in 1 Corinthians 1:3. An extensive paragraph from this excursus summarizing Paul’s understanding of grace merits citation in full:

As one begins reading the commentary proper, chapter by chapter and passage by passage through Paul’s letter, one is treated early on to a marvelous excursus on grace, which should warm any Christian’s heart, after Paul’s first use of the term in 1 Corinthians 1:3. An extensive paragraph from this excursus summarizing Paul’s understanding of grace merits citation in full:

For Paul, in its deepest theological sense, charis refers to God’s positive predisposition to favor and bless his children. But, because God’s actions are motivated by grace, they are freely given (Rom. 4:4; 11:6). The core meaning of charis as “a gift” should always be remembered. Indeed, grace is expressed through a gift, gesture, or benefit that is neither merited nor earned. Therefore, since God calls a person to grace—that is, God gives it to him (Gal. 1:6, 15)—the individual has no claim on it or is it given because he deserves it. Rather, it predates the individual’s goodness or righteousness and is extended to him even as a sinner (Rom. 3:23–25; 5:10; 1 John 4:19; compare Rom. 11:32; Gal. 2:17–21). Its power, however, is displayed in the overcoming of sin (Rom. 5:20–21). It is important to understand that grace is unilateral and independent of the receiver. In every case, God makes the first move. It is this that makes it possible for the individual to respond graciously and so move “from grace to grace” (D&C 93, heading). But the absolutely essential element of that transaction is that God moves first in each instance, giving the person gracious gifts and then additional gifts, rather than the person first exercising his or her goodness and then being rewarded with earned blessings.[1]

There is not a word here that Evangelical Christians should not welcome and embrace wholeheartedly. Indeed, later on in this same excursus, our authors clarify 2 Nephi 25:23 (“[for] it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do”) as meaning above and beyond all we can do. It is not that we do all we can, and then God’s grace kicks in. After all, they explain, it is always theoretically possible that we could have done more so that we would never experience God’s grace if he waited to bestow it until we had done our very best possible. Alma 24:10-12, moreover, shows that all we can do is, in fact, to “come before the Lord in reverent humility, confess our weaknesses, and plead for his forgiveness, for his mercy and grace.”[2]

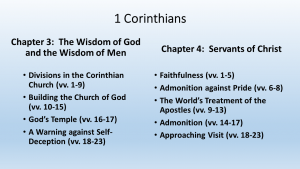

The treatment of the foolishness of the cross in 1 Corinthians 1:18-2:5 is equally powerful and aptly described, as is Paul’s determination to know nothing but Christ and him crucified in 1 Corinthians 2:2. Here, Paul is particularly combating the Sophist philosophers of his day who proliferated in Corinth, emphasizing style above substance in their oratory. Paul demonstrates in his epistles that he can use very effective rhetorical devices, but it is the Spirit’s power, not those devices, on which he relies if he is to produce anything of value for Christ and his kingdom. With various other commentators, Draper and Rhodes take the spiritual person in 1 Corinthians 2:6-16 to be a subset of all believers, as it clearly is in 1 Corinthians 3:1-23. But, with a majority of recent commentators, it seems better to see that 1 Corinthians 2:6-16 contrasts all Christians with all non-Christians (spiritual vs. natural people, to use the KJV language), with Paul introducing a type of contrast among Christians only in chapter 3 (spiritual vs. carnal Christians). In chapter 3, then, there are two, but only two types of believers on Judgment Day when “each person’s work will be tried as by fire, that is, it will be put to the test to show its quality. That quality is determined largely by the motivation that stood behind it. If its purpose was for pride, self-promotion, fame, or power, it will fail the test. If it was to promote the ends of the kingdom, bring people to Christ Jesus, or for the glory of God, it will pass.”[3]

In chapter 4, Draper and Rhodes rightly recognize how the beginning of verse 8 is dripping with irony and sarcasm as Paul rebukes the Corinthians for their overly exalted self-estimation. “You already have enough! You already are rich!” (BYU Rendition). The next half verse makes his irony clear: “Indeed, I wish you had become kings so that we might rule with you.” Instead, the apostles suffer and are mistreated in just about every way imaginable. As in the New International Version (NIV), the BYU Rendition powerfully captures the force of verse 13 and of Paul’s self-depiction by rendering the Greek, “we have become the scum of the earth”!

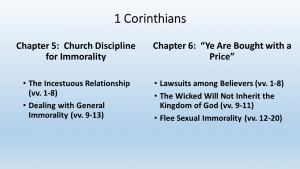

The waters become a little muddier with 1 Corinthians 5. It is true that about half of the commentators of all theological stripes see the incestuous man whom Paul disciplines by proxy here actually dying (excommunicated “for the destruction of the flesh”—v. 5). But the blood atonement notion of Joseph Fielding Smith that Christ’s death was insufficient to cover certain kinds of sins, so that this man’s death was what atoned for him, goes well beyond what the text ever says. As I understand it, it is not a doctrine taught in the Standard Works, it is not accepted by all Latter-day Saints, so I am surprised that our authors feel compelled to support it. They have already noted, moreover, that “flesh” here most likely means sinful nature, not body. Why they don’t proceed to interact with the other main interpretation of this passage, then, puzzles me. Surely it is more likely that this offender is the same man who has repented in 2 Corinthians 2 and 7, and whom Paul requests the Corinthians reinstate lest his grief be excessive. In that case, he clearly didn’t die, much less atone for his own sin.

The waters become a little muddier with 1 Corinthians 5. It is true that about half of the commentators of all theological stripes see the incestuous man whom Paul disciplines by proxy here actually dying (excommunicated “for the destruction of the flesh”—v. 5). But the blood atonement notion of Joseph Fielding Smith that Christ’s death was insufficient to cover certain kinds of sins, so that this man’s death was what atoned for him, goes well beyond what the text ever says. As I understand it, it is not a doctrine taught in the Standard Works, it is not accepted by all Latter-day Saints, so I am surprised that our authors feel compelled to support it. They have already noted, moreover, that “flesh” here most likely means sinful nature, not body. Why they don’t proceed to interact with the other main interpretation of this passage, then, puzzles me. Surely it is more likely that this offender is the same man who has repented in 2 Corinthians 2 and 7, and whom Paul requests the Corinthians reinstate lest his grief be excessive. In that case, he clearly didn’t die, much less atone for his own sin.

With chapter 6, things seem back on track again. Draper and Rhodes recognize that Paul does not prohibit all redress for wrongs in forbidding secular lawsuits by Christians against Christians; it is merely that they should be settled within the church instead (1 Cor. 6:1-8). Our authors realize that the warning against people who persistently do evil not inheriting the kingdom of God (vv.9-11) is not a list of some kind of unforgivable sins, but refers to those who refuse to repent of them. And the commentary rightly notes that the two words used for homosexual activity refer to the more active and the more passive partner in homosexual acts. No orientation is being condemned, just the way in which some choose to act upon it. Near the end of the discussion, Gordon B. Hinckley is appropriately quoted: “Our hearts reach out to those who struggle with feelings of affinity for the same gender. We remember you before the Lord, we sympathize with you, we regard you as our brothers and our sisters. However, we cannot condone immoral practices on your part any more than we can condone immoral practices on the part of others.”[4]

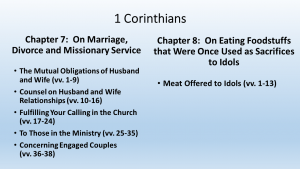

1 Corinthians 7 presents the interpreter with a hornet’s nest of problems, but our commentators navigate their way through it reasonably deftly. Like many modern translations, the BYU Rendition puts “it is good for a man not to have sexual relations with a woman” in verse 1 in quotation marks. It is better understood as a statement or slogan some of the Corinthians were making than something Paul could have said, at least not without significant qualification. Gordon Fee’s New International Commentary on the New Testament, which Draper and Rhodes cite, is persuasive here. Or as J. C. Hurd put it already in the 1960s, this chapter shows Paul’s “yes, but” logic. As much as he can, Paul affirms a faction that was over-exalting celibacy, but realizes this requires a certain giftedness or calling. By no means can it be made the norm.

1 Corinthians 7 presents the interpreter with a hornet’s nest of problems, but our commentators navigate their way through it reasonably deftly. Like many modern translations, the BYU Rendition puts “it is good for a man not to have sexual relations with a woman” in verse 1 in quotation marks. It is better understood as a statement or slogan some of the Corinthians were making than something Paul could have said, at least not without significant qualification. Gordon Fee’s New International Commentary on the New Testament, which Draper and Rhodes cite, is persuasive here. Or as J. C. Hurd put it already in the 1960s, this chapter shows Paul’s “yes, but” logic. As much as he can, Paul affirms a faction that was over-exalting celibacy, but realizes this requires a certain giftedness or calling. By no means can it be made the norm.

At each juncture along the way, Paul significantly qualifies the perspectives of these overly zealous abstainers from sex: within marriage, such abstention should be very limited and purposive (vv. 3-7); for widows and widowers (the more likely translation of the masculine noun in v. 8 than merely KJV’s “unmarried”), it can be more natural, but remarriage is also permitted (vv. 8-9); non-Christians who insist on divorcing and leaving a Christian partner need not be stopped, but if the marriage can be kept intact, there are spinoff blessings for all parties, including children (vv. 10-16). Those not yet married need not marry because of the present distress, which Draper and Rhodes take to mean the coming apostasy, but which could also mean that the time left on earth is short (v. 29), but they scarcely sin by marrying, as the pro-celibacy faction in Corinth would have imagined (vv. 25-35). And the engaged need not get married, but it is certainly appropriate if they do (vv. 36-38). Draper and Rhodes think these last two provisions are merely the postponement of marriage so that the man can go on missionary service, following the JST, but this goes well beyond anything the text or its context suggests. Once Joseph Smith decided to make marriage more mandatory than the Bible does, he had to find some way to explain these otherwise problematic passages for his perspective.

It is a bit misleading, then, for our authors to write that “C. S. Lewis caught the significance of the Savior’s teachings. He taught that single humans are but half beings whom God designed to be combined in pairs.”[5] Lewis did indeed speak of the male and female genders “designed to be combined in pairs,” but, as Draper and Rhodes acknowledge in their footnote, it was Plato who used the expression “half being.” Lewis never calls a human being a half being, and given God’s creation of every person in his image, this claim would be untrue to both Jewish and Christian theology. It is the kind of claim that, sadly, single people too often hear within all different churches, making them feel like second-class citizens at best.

The problem of the weaker and stronger brothers and sisters in the context of eating food sacrificed to idols in chapter 8 is treated well in the commentary. The exposition properly disabuses those in any religious tradition who emphasize rights and entitlements more than responsibilities and sacrifices for the sake of others. The only caveat I would introduce here is maybe not even one that applies much in Mormon circles; I know only that Evangelicals need it! Paul’s implied definition of the weaker sibling here is the person who, when seeing another believer free to participate in some morally neutral activity, is emboldened either to imitate that believer without a clear conscience or to go beyond the morally neutral matter into something that is unambiguously sinful (vv. 7-13). In my circles, however, these principles are often erroneously applied to what one writer has dubbed “the professional weaker brother”—that is, the person who makes a habit of objecting to all kinds of new and creative activities, some of them even designed to help believers relate better to non-believers for evangelistic purposes. Yet these professional weaker brothers would never in a million years imitate the practices to which they object, much less go beyond them into actual sinful behavior. Other biblical passages remind us that we must not deliberately offend such people willy-nilly, but these people are not those Paul calls weaker brothers or sisters, so it is invalid to apply Paul’s teaching here to those individuals.

Perhaps the most interesting question in chapter 9 to emerge from the commentary is whether the first-person plural in verse 5 indicates that Paul was married even when he wrote the letter, rather than widowed as 1 Corinthians 7:8-9 seems to suggest. In other words, when Paul asks if it is only “we” (Barnabas and Paul) who don’t have the right to take a believing wife along with them, is he indicating that he is still married? Draper and Rhodes have already made a good case for this option in their introduction, and it is one that other commentators ought to consider more seriously. What Paul would then be implying is that Barnabas and he simply left their wives at home during their missionary travels.

Perhaps the most interesting question in chapter 9 to emerge from the commentary is whether the first-person plural in verse 5 indicates that Paul was married even when he wrote the letter, rather than widowed as 1 Corinthians 7:8-9 seems to suggest. In other words, when Paul asks if it is only “we” (Barnabas and Paul) who don’t have the right to take a believing wife along with them, is he indicating that he is still married? Draper and Rhodes have already made a good case for this option in their introduction, and it is one that other commentators ought to consider more seriously. What Paul would then be implying is that Barnabas and he simply left their wives at home during their missionary travels.

Draper and Rhodes also deal flawlessly with Paul’s puzzling use of the Old Testament in 1 Corinthians 9:10. Having quoted Deuteronomy 25:4 about not muzzling oxen while they tread out grain in verse 9, Paul then applies this principle to providing financial support for Christian leaders. The KJV raises all sorts of questions with its rendering, “or saith he it altogether for our sakes?” as if the Mosaic Law never intended to refer to cattle at all! But the BYU Rendition is the better translation: “Isn’t he certainly speaking for our benefit?” (italics mine). Of course, the law was about oxen, but Paul sees a natural parallel in the human realm. He is not providing Deuteronomy’s original meaning, but giving a valid contemporary application. Draper and Rhodes explain,

The preposition δία (dia) with the accusative indicates cause, “for our sakes” or “for us.” By the use of that word, Paul moved the application of that scripture from the Old Testament to his own time period. The word shows that the Apostle took the verse in its higher context of dealing more with humankind than with animals. The Apostle accorded the scripture a proper place in showing how the Saints were to act generally and also how it was to be applied to the specific situation he was in.[6]

In the context of 1 Corinthians 10:13 on resisting temptation, our commentators offer an excellent extended quote from a 1989 Ensign article by Joseph Wirthlin. It ends with these words: “be sure you understand that God will not allow you to be tempted beyond your ability to resist. He does not give you challenges that you cannot surmount. He will not ask more than you can do, but may ask right up to your limits so you can prove yourselves. The Lord will never forsake or abandon anyone. You may abandon him, but he will not abandon you. You never need to feel that you are alone.”[7] Perhaps paradoxically, in Evangelical circles, these principles are often overly simplified and boiled down to “God will never give you more than you can handle” and communicated in such a way as to suggest we can handle them on our own. Draper and Rhodes make Paul’s intent very clear: the only sense in which it is true that God never gives us more than we can handle is that with the temptations, he gives us the empowerment, if we let him, not to give in to them.

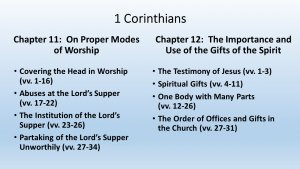

1 Corinthians 11:1-16 is perhaps the most challenging segment of Paul’s entire letter to interpret. What is going on with head coverings or their absence on women and men, and why does it matter? All interpreters recognize a certain amount of situation-specific instruction here, as do Draper and Rhodes. Four observations on particularly tricky parts of this passage, in my opinion, are exactly on target. First, that women are allowed to pray and prophesy in the congregation (v. 5) certainly gives permission for women to instruct men, as well as other women, in the weekly worship service, a point Latter-day Saints understand better than some very conservative Evangelicals.

1 Corinthians 11:1-16 is perhaps the most challenging segment of Paul’s entire letter to interpret. What is going on with head coverings or their absence on women and men, and why does it matter? All interpreters recognize a certain amount of situation-specific instruction here, as do Draper and Rhodes. Four observations on particularly tricky parts of this passage, in my opinion, are exactly on target. First, that women are allowed to pray and prophesy in the congregation (v. 5) certainly gives permission for women to instruct men, as well as other women, in the weekly worship service, a point Latter-day Saints understand better than some very conservative Evangelicals.

Second, women are created in God’s image every bit as much as men, accounting for the lack of symmetry in verses 7-8: “[man] is the image and glory of God: but the woman is the glory of the man.” Woman is not created in the image of man, but also in the image of God. And the statement that “woman is the glory of the man” is not a diminution of her role, but an acknowledgment that “it is she who brings the man glory. Without her, he would be hard pressed to receive any”![8] Third, the correct translation of the beginning of verse 10 is “for this reason a woman ought to have control over her head,” as the BYU rendition puts it. This is not some feminist slogan giving her independent authority, but a summary of Paul’s commands thus far in the passage. For the sake of not sending culturally misleading signals by her coiffure or her appearance, the woman in church must wear the proper head covering. Fourth, Paul immediately adds “because of the angels,” most likely because Jews believed them to be watchers and guardians of God’s people at worship.

The second half of chapter 11, on the Eucharist or Sacrament Service, is not fraught with as many exegetical difficulties. The biggest issue is cutting through the centuries of overlay of theological interpretation and reading the passage afresh in its original context. It is certainly possible with our authors that when Paul berates the Corinthians for eating and drinking unworthily (v. 27), it is because their “conduct is not matching the seriousness and solemnity of the occasion.” But the Passover, on which this festival built, like the Messianic Banquet which it foreshadows, are also occasions of great joy and celebration. In context, the Corinthians’ sin was overeating and overdrinking at the expense of the poorer Christians in their gathering (vv. 21-22). Most Christian churches would experience considerable distress if their leaders consistently taught that the people who should refrain from the Lord’s table or sacrament are those who are not adequately concerned about their poorer fellow believers!

Chapter 12 introduces the topic of spiritual gifts, stressing the diversity within the unity of the body of Christ. The only debate of great significance for interpreters here is whether all the gifts Paul discusses are still in force today. Quite different from the milieu in Joseph Smith’s day, today’s Pentecostal churches and movements have spread widely around the globe, and the vast majority of scholarly commentary on 1 Corinthians recognizes that there are no valid reasons for relegating the so-called charismatic gifts just to the first century or apostolic era. None of them ever entirely ceased, and since the Azusa Street Revival of 1906 in Southern California, all of them have proliferated in increasing abundance and not merely in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

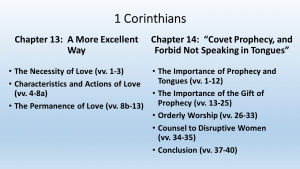

Chapter 13, of course, is often treated as a self-contained poem or rhapsody about love. It is no doubt that here is where commentators most feel their own impoverished abilities to add anything of great value to Paul’s powerful, inspired words. What can be lost sight of, however, is that chapter 13 falls in between chapters 12 and 14! That is to say, Paul is still teaching on the topic of spiritual gifts, but he is insisting that without love, the gifts prove worthless and that love will abide into eternity when the gifts have finally ceased. Draper and Rhodes nicely summarize Paul’s understanding of agape (“love”) in an excursus on the topic. “It will have nothing to do with anything driven by ego or self-interest. Its touch brings to the recipient a new center, a transformation from concern for self to a concern for others and doing the will of the Master.” Again, “the result is a total disinterest in what would be personal advantage. Though advantage may come, that possibility in no way influences love’s action. The Savior did not come to please himself but to please God through assistance to others (Rom. 15:3). The disciple should do the same (1 Cor. 10:24). Such action is the truest sign of pure love.”[9] I like to quote my former pastor and long-time missionary to the Upper Amazon Basin of Brazil, Richard Walker: “Love is the unsolicited giving of the very best you have on behalf of another regardless of response.”

Chapter 13, of course, is often treated as a self-contained poem or rhapsody about love. It is no doubt that here is where commentators most feel their own impoverished abilities to add anything of great value to Paul’s powerful, inspired words. What can be lost sight of, however, is that chapter 13 falls in between chapters 12 and 14! That is to say, Paul is still teaching on the topic of spiritual gifts, but he is insisting that without love, the gifts prove worthless and that love will abide into eternity when the gifts have finally ceased. Draper and Rhodes nicely summarize Paul’s understanding of agape (“love”) in an excursus on the topic. “It will have nothing to do with anything driven by ego or self-interest. Its touch brings to the recipient a new center, a transformation from concern for self to a concern for others and doing the will of the Master.” Again, “the result is a total disinterest in what would be personal advantage. Though advantage may come, that possibility in no way influences love’s action. The Savior did not come to please himself but to please God through assistance to others (Rom. 15:3). The disciple should do the same (1 Cor. 10:24). Such action is the truest sign of pure love.”[9] I like to quote my former pastor and long-time missionary to the Upper Amazon Basin of Brazil, Richard Walker: “Love is the unsolicited giving of the very best you have on behalf of another regardless of response.”

Chapter 14 narrows Paul’s focus to the two particularly problematic gifts in the Corinthian church—prophecy and tongues. His overall message is clear: prefer prophecy because it is more immediately intelligible. Draper and Rhodes handle this well, including the puzzling verse 22, where tongues are said to be signs for unbelievers, not for believers. This is not because tongues are more evangelistic in nature; the context makes it clear that some outsiders coming to the church will hear tongues and go away claiming the believers are mad! Rather, in view of the quotation of Isaiah 28:11-12 in the previous verse, in which the foreign tongues of the Assyrians are a sign of judgment in Israel, tongues likewise must be functioning as a sign of judgment in Corinth when they are used without interpretation.

1 Corinthians 14:34-35 forms the other huge exegetical conundrum in this chapter. Draper and Rhodes survey several of the proposals for explaining how Paul can seemingly silence all women all the time in church, especially after his words to the contrary in chapter 11. With more conservative or “complementarian” evangelicals, they see the restriction as limited to presiding over the congregation. After all, the context of these two verses is the discussion of tongues, their interpretation, prophecy, and its evaluation, which would have ultimately come down to the congregational leaders to determine. Worthy of more consideration, nevertheless, is the “egalitarian” understanding that sees a situation-specific nature to Paul’s commands, given how little access women had to formal religious education and the likelihood that they would have asked basic questions, thus disrupting worship, which were better dealt with in their homes.

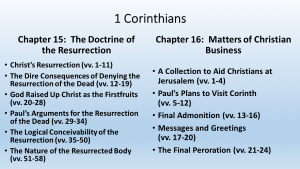

Chapter 15 creates yet another high point in 1 Corinthians with its lofty teaching about the truth of the bodily resurrection of Jesus and of the coming bodily resurrections of all of his true followers. Our commentators’ treatment overall is both accurate and incisive. The two main points where virtually anyone would disagree who was not already committed to Joseph Smith’s interpretations are on the baptism for the dead (v. 29) and on the celestial, terrestrial, and telestial kingdoms (derived, supposedly, from v. 41). It is true, as certain early church Fathers noted, that there were a handful of Greek Christians in and around Corinth practicing proxy baptism, though only for those known to have been Christians in this life who died unbaptized. Paul, however, neither commends nor commands the practice. Instead, for the sake of argument, he simply assumes its legitimacy and then shows that it presupposes belief in a bodily resurrection. After all, immediately after this verse, Paul reasons in exactly the same way from the persecution and hostility he has experienced (vv. 30-32), and he is neither commending it nor commanding that people seek persecution, but simply pointing out the logical consequences of his experiences. Proxy baptism need not have been either heretical or divinely instituted— the two options Draper and Rhodes leave us with. There are several intermediate possibilities.

Chapter 15 creates yet another high point in 1 Corinthians with its lofty teaching about the truth of the bodily resurrection of Jesus and of the coming bodily resurrections of all of his true followers. Our commentators’ treatment overall is both accurate and incisive. The two main points where virtually anyone would disagree who was not already committed to Joseph Smith’s interpretations are on the baptism for the dead (v. 29) and on the celestial, terrestrial, and telestial kingdoms (derived, supposedly, from v. 41). It is true, as certain early church Fathers noted, that there were a handful of Greek Christians in and around Corinth practicing proxy baptism, though only for those known to have been Christians in this life who died unbaptized. Paul, however, neither commends nor commands the practice. Instead, for the sake of argument, he simply assumes its legitimacy and then shows that it presupposes belief in a bodily resurrection. After all, immediately after this verse, Paul reasons in exactly the same way from the persecution and hostility he has experienced (vv. 30-32), and he is neither commending it nor commanding that people seek persecution, but simply pointing out the logical consequences of his experiences. Proxy baptism need not have been either heretical or divinely instituted— the two options Draper and Rhodes leave us with. There are several intermediate possibilities.

Verse 41 brings us to the other uniquely Mormon doctrine derived, in part, from 1 Corinthians 15. Here is where Joseph Smith, in part, finds support for his three kingdoms, one with the glory like that of the sun, one with the glory of the moon, and a third with the glory of the stars. But a careful reading of the entire context shows that Paul is not primarily contrasting the varying glories of the heavenly bodies with one other. Instead, he is contrasting the glory of the heavenly bodies with those of various earthly bodies (v. 40). The principles he derives from his analogy likewise all contrast our earthly bodies with our resurrection bodies, rather than distinguishing among three different types of resurrection existence (vv. 42-54).

If it be argued that Paul does indeed observe that the sun, moon, and stars have different degrees of glory, then we should note that he also declares that the stars all differ from each other in glory. If we are to derive three different kinds of resurrection existence from the first clause of verse 41, then we should derive an infinite number of kinds of eternal glories from the second clause. Ironically, this is exactly what Calvinists have taught with their notion of endless degrees of reward in the life to come, based on one’s works in this life. I am convinced, rather, by the Lutheran approach that does not read this much into either half of the verse, but recognizes just Paul’s main point. Just as there are all kinds of “bodies” that differ from each other in our current experience of the universe, we should not find it strange to imagine God being able to create a perfected human body for each of us in the life to come.

Little needs to be said about 1 Corinthians 16. In verses 1-4, Paul anticipates his much more detailed instructions about the collection for the impoverished saints in Jerusalem in 2 Corinthians 8-9. Then, he closes the letter with reference to his and others’ travel plans, final greetings, and closing exhortations (vv. 5-24). Perhaps I may be permitted one final textual comment on the holy kiss in verse 20. Nothing Draper or Rhodes say ever suggests they think that the JST represents the original text of the Bible that our existing Hebrew and Greek manuscripts altered at some early date, making the KJV and modern English translations less reliable. But some Mormons have, at times, imagined this. 1 Corinthians 16:20 offers a classic disproof of this notion. No scribe, translator, prophet, seer, or anyone else would have ever changed “greet one another with a holy salutation” (JST, offering a timeless, cross-cultural principle) to “greet one another with a holy kiss” (the original Greek and all other bona fide translations, presenting something that works well only in certain cultures). On the other hand, it makes perfect sense to change “kiss” to “salutation” to create a timeless principle.

Draper and Rhodes capture this accurately as they comment that the kiss “was a show of respect and honor and often used by disciples to honor their teachers. The JST changes this word to ‘salutation,’ thus making Paul’s request conform more to western and modern practices.”[10] The JST is not a translation; it is an interpretation, at times with supplementary material added, and it deserves to be called that in twenty-first century English. The BYU Rendition is a highly accurate translation, on the other hand, and it deserves to be called a translation. No one should think that the JST is preferable to the BYU Rendition at any point, despite claims to the contrary. But, of course, it is easier for me to say this as an outsider than for those inside Mormonism, even those who agree with me.

As our commentators close their volume, they observe,

the final two verses emphasize Paul’s mutual themes of χάρις (charis), “grace,” and ἀγάπη (agapē), “love.” Indeed, grace has been a bright silver thread that has run through the tapestry of the whole epistle. It is from the grace of God that Christ-like love flows, a love that is the golden thread that has bound the fabric of the whole piece together.

Such love is more than a transient feeling but an enduring attitude of concern and care that pushes one to do whatever is necessary for the spiritual and eternal well being of the other. Paul knows that love personally and expresses it with both sincerity and solemnity. In spite of all the problems certain members of the Church have caused him, it has not lessened his love for them. He loves them all—not only the weak but also the strong, not only his friends but also his detractors.

He has preached nothing but “Christ, and him crucified” (2:2), but he has explored all the ramifications of this doctrine. In doing so, he has exposed and highlighted the underlying, overreaching, final, and most beautiful of its aspects–that of self-sacrificing love. Paul, being filled with that supernal virtue, loves the Corinthian Saints ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ (en Christō Iēsou), “in Christ Jesus,” the source of all such love.[11]

With this, the commentary, like Paul’s letter, comes to a close. These are fitting final paragraphs to end the work on an inspiring note and to summarize the main themes of the epistle.

The editors of the BYU New Testament Commentary series have made it clear that they want to present to the public rigorous biblical scholarship and edifying personal devotion. Usually, these come in two separate, consecutive sections of the commentary on each passage, labeled “Notes and Comments” and “Analysis and Summary,” respectively. Much of the time, the distinctively Mormon reflections are found only in the second of these sections. This is probably the best that can be done, given the desire to continue to present not just relevant cross-references from the Standard Works, but a wide swath of quotations and opinions from key LDS leaders throughout Mormon history.

The occasional disconnect between these quotations and what the Bible actually says are not as common or as glaring as they often seemed to me to be while I was working through the Revelation commentary. Even then, the disconnect hardly struck me on a majority of the quotations of LDS Authorities, just on a noticeable minority. I sense this disjunct even less in 1 Corinthians. Partly, this is due to my understanding of how readily Joseph Smith, for example, could have derived baptism for the dead and the three kingdoms from the relevant passages in 1 Corinthians 15, even though I find such derivation unpersuasive. Partly, it is because the other instances when it occurs affect the interpretation of more minor details within a passage rather than their main points. More so than with Revelation, there were occasions where I thought to myself, “that’s an interpretation worth considering,” as with the debate over whether Paul could have still been married when he wrote 1 Corinthians.

I understand that the primary audience for this series is the LDS community. But given the original desire of some to have the series also be sufficiently scholarly and integrated in perspective that it might commend itself to the outside world as it studies the New Testament to determine its meaning and not just to see what the LDS party-line thinks about its meaning, the commentary on 1 Corinthians has taken a few additional steps toward this goal. And again, compared to anything else the Mormon world has ever produced, these volumes have made major advances.

I do not believe there is a celestial kingdom separate from a terrestrial kingdom, with both of those separate from a telestial kingdom. Mormons, of course, do. In that light, given the fidelity of this series to mainstream LDS thought, this is truly a celestial commentary. There is nothing that would place its authors in jeopardy of making it only to the terrestrial or telestial kingdoms. Given the light years of advances beyond what previous Mormon projects of this nature have made, it remains equally celestial. For these reasons, I have entitled this review, “A Celestial Commentary on 1 Corinthians.” In terms of the whole gamut of commentaries available today on 1 Corinthians, if celestial can be used simply as a synonym for that which is the most excellent, accurate, and helpful overall; if terrestrial can mean that which is regularly on target but has some glitches and oddities in it; and if telestial can be redefined as that which has some truth and value in it but overall isn’t all that great, then I still would have to rank Draper and Rhodes’ work as terrestrial. And if that doesn’t seem like high enough praise, I would add that many works— especially of the older, shorter works from historic Christian circles, in my opinion— merit only the label telestial!

Craig L. Blomberg

Distinguished Professor of New Testament

Denver Seminary

July 31, 2015

[1] Charis in the Epistles of Paul, in Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians, by Richard D. Draper and Michael D. Rhodes.

[2] Saved by Grace after All We Can Do, in Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians, by Richard D. Draper and Michael D. Rhodes

[3] Building the Church of God, in Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians, by Richard D. Draper and Michael D. Rhodes.

[4] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Stand Strong Against the Wiles of the World,” Ensign, November 1995

[5] Excursus on Marriage and Divorce, in Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians, by Richard D. Draper and Michael D. Rhodes

[6] The Privileges of those Who Preach the Gospel, in Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians, by Richard D. Draper and Michael D. Rhodes

[7] Other General Authorities, chapter 10, in Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians, by Richard D. Draper and Michael D. Rhodes

[9] Excursus on Love/Charity, in Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians, by Richard D. Draper and Michael D. Rhodes

[10] Messages and Greetings, in Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians, by Richard D. Draper and Michael D. Rhodes

[11] The Final Peroration, in Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians, by Richard D. Draper and Michael D. Rhodes